Breast Cancer: Everything You Need to Know

We’ve got the doctor-approved details on breast cancer causes, symptoms, treatments, and other facts and tips that can make life facing breast cancer easier.

WHETHER YOU’VE JUST been diagnosed or worry you could have breast cancer, you’re probably nervous and confused—but you are not alone. We've talked with the top experts in the field to bring you the very latest information on the causes and treatments for the condition, as well as helpful lifestyle changes that can help you keep living your life while battling this challenging disease. We’re sure you’ve got a lot of questions... and we’re here to answer them.

How Common Is Breast Cancer—and How Does it Form?

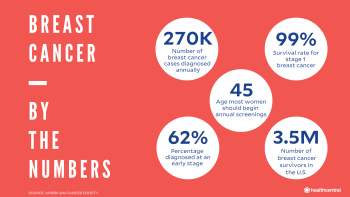

You likely already know some breast cancer basics—since there’s a good chance there is someone in your life who’s had it. While anyone can be diagnosed with breast cancer, breast cancer is second only to skin cancers as the most common malignancy in women—about 284,200 cases are diagnosed each year, accounting for approximately 30% of all cancer cases, according to the American Cancer Society. Although it happens much less often, men can also develop breast cancer. In fact, in 2019 Beyonce’s dad became one of the 2,650 men in the U.S. who are diagnosed annually.

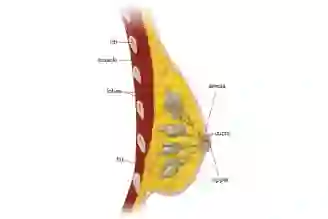

No matter who you are, breast cancer begins in a similar fashion: A rogue cell multiples in ways it’s not supposed to, eventually forming a tumor. But to really understand the different types and stages of breast cancer, it helps to have an image in your mind of where a tumor starts and how it grows.

What Are the Stages of Breast Cancer?

Now, for a little background anatomy. The main structures of the breast are:

Milk glands (called lobules), the ducts that carry milk. A girl's ovaries make female hormones during puberty, which causes breast ducts to grow and lobules to form at the ends of ducts, according to cancer.org. Boys and men normally have low levels of female hormones, and breast tissue doesn't grow much, during, or after puberty. Men's breast tissue does have ducts, but only a few (if any) lobules.

Fatty and fibrous tissue that make up most of the breast.

Most breast cancers start in the glands or ducts.

Once breast cancer is found, doctors will give it a stage—from stage 0 to stage IV—depending on the extent of the disease, what the prognosis is, and which treatments will work best. Within each stage, there are further classifications depending on things like tumor size and lymph-node involvement, usually indicated by doctors with the letters A, B, and C.

Stage 0

Also called ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), stage 0 tumors are abnormal cells that form inside the duct (“in situ” means remaining in place).Current research suggests that in many cases, these cells will not grow any further or cause problems for the patient. Some even consider this non-invasive form of DCIS precancer.

The catch? About 20% to 30% of the time, these cells continue their out-of-control ways and push into tissues outside of the duct (this is called “invasive” cancer). Unfortunately, there is no sure way to know which type of DCIS you have, which is why even stage 0 breast cancers are treated (more on this below).

Stage I

Stage I is the earliest possible stage of invasive breast cancer. Cancers caught at this stage are curable and treatable: The five-year survival rate—meaning, the number of women who are alive five years after diagnosis—is an incredible 99%. Stage I is divided into two subcategories.

Stage IA. At this point, the tumor isn’t bigger than 20 millimeters (2 cm) and hasn’t spread to underarm lymph nodes.

Stage IB. In this stage, there may not be any evidence of a tumor in the breast, or the tumor there is smaller than 20 mm. That said, a diagnosis with stage IB does mean that cancer has spread to the lymph nodes, with that cancer being between 0.2 mm and 2 mm in size.

Stage II

These invasive tumors are really trying to stake their claim. They’re generally between 20 mm and 50 mm and may have spread into a few lymph nodes under the arm. But deep breath. The five-year survival rate for stage II cancer is a still at least 86%. Stage II is also divided into two subcategories:

Stage IIA. In stage IIA, it’s possible that there is no evidence of a breast tumor, but cancer bigger than 2 mm has spread to one to three underarm lymph nodes or lymph nodes near the breast bone. Other possible scenarios in this subcategory include finding a breast tumor that is 20 mm or smaller that has spread to one to three underarm lymph nodes, or a tumor between 20 mm and 50 mm that hasn’t spread to underarm lymph nodes.

Stage IIB. In this subcategory, the tumor may be between 20 mm and 50 mm and has spread to one to three underarm lymph nodes. Tumors bigger than 50 mm that haven’t spread to underarm lymph nodes are also classified as stage IIB.

Stage III

At this point, the tumor is likely growing into a fairly substantial size—think anywhere between a single grape to a lime—and/or cancer cells have made their way into several lymph nodes, either under the arms or as far away as the collarbone. This stage also includes cancers that have directly invaded the chest wall or have formed skin nodules or ulceration.

Stage IIIA. In this substage, the breast cancer can be any size, but it must have spread to four to nine underarm lymph nodes or to internal mammary lymph nodes but not any other parts of the body. Tumors greater than 50 mm in size that have spread to one to three underarm lymph nodes also fall into this subcategory.

Stage IIIB. In stage IIIB, the tumor has spread to the chest wall or resulted in breast swelling or ulcers. It’s also possible that it has spread to up to nine lymph nodes (either underarm or internal mammary ones) but no other parts of the body.

Stage IIIC. In this stage, you may have breast tumors of any size and the cancer has spread to 10 or more underarm lymph nodes, internal mammary lymph nodes, or collarbone lymph nodes—but not any other parts of the body.

Stage IV

This most advanced form of breast cancer, known as metastatic, has spread to the bones and/or organs, such as lungs, liver, or brain. The most difficult part about this diagnosis is that it’s not considered curable. However, in some people, progression of the disease can be slowed or even stopped by a series of medications and other treatments, and the disease becomes more of a chronic illness. The five-year for this stage is 28%, which we know isn’t easy to see, but here’s what you must remember about these stats: Yes, they are scary, but you are not a number. There are women alive today who have been living with metastatic breast cancer for decades.

What Are the Types of Breast Cancer?

In addition to describing breast cancer by stages, there are also other subcategories of this cancer that your doctor may include in your diagnosis. All of these different terms and ways of describing your breast cancer can get confusing—so let’s break them down. Many of these terms are based on which part of the breast the tumor begins in.

Carcinoma

The majority of breast cancers are carcinomas. This means that the tumors start in epithelial cells, which are a type of cell that line the body’s organs and tissues. Usually, carcinomas in the breast are adenocarcinomas. These are tumors that start in the milk ducts or milk producing glands (lobules) in the breasts.

Ductal Carcinoma

One major category of adenocarcinomas are called ductal carcinomas. These are cancers that start in the cells of the milk ducts in the breast. The earliest form of ductal carcinoma is called ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). Again, “in situ” means “in place,” and in this case means the cancer is only in the milk ducts of the breast and hasn’t spread to other parts of the body. It’s a very curable type of breast cancer. Once the cancerous cells spread beyond the milk ducts where they first form into other tissues of the breast, the cancer becomes what is called an invasive ductal carcinoma.

Invasive Ductal Carcinoma (IDC)

This is actually the most common form of breast cancer. It affects about 70% to 80% of people with breast cancer. There are also several subtypes of IDC.

Cribriform carcinoma. With this form of IDC, cancerous cells find their way into the breast’s connective tissue. This subtype is characterized by Swiss cheese-like holes between the cancer cells. This type of cancer makes up around 5% to 6% of invasive breast cancers.

Medullary carcinoma. This form of IDC is quite rare—about 3% to 5% of people with breast cancer have this this form. Its name comes from the appearance of the tumor, which looks like the fleshy tissue in the part of your brain called the medulla. It’s most common in women in their 40s and 50s and in women with a BRCA1 gene mutation. Typically, it responds well to treatment.

Mucinous carcinoma. This rare carcinoma (also called colloid carcinomas) makes up about 2% to 3% of invasive breast cancer cases. With mucinous breast cancer, the cancer cells are surrounded by mucin, which is a slimy ingredient in mucous. Usually, these cancers are found in post-menopausal women. Thankfully, this subtype tends not to be very aggressive or spread to the lymph nodes compared with other types, and it typically responds to treatment well.

Tubular carcinoma. These small, slow-growing tumors used to make up only about 1% to 4% of invasive breast cancer diagnoses, but that number has been growing as screening has improved and is better able to detect this type of cancer. Its name comes from the tube-like shapes inside the tumor cells. The average age of diagnosis for this subtype is the early 50s, and it’s usually not very aggressive and has a good outlook for treatment.

Papillary carcinoma. Under 1% to 2% of invasive breast cancers are papillary carcinomas, so named because of the finger-like growths called papules on the tumor cells. This type is more common in older, post-menopausal women.

Invasive Lobular Carcinoma (ILC)

This cancer makes up about 10% of all invasive breast cancers and is the second-most common form of breast cancer in the U.S. Lobular carcinomas start in the milk-producing glands of the breast, called lobules. Compared with IDCs, ILCs can be harder to catch on mammograms and other screening tests.

Less Common Cancers and Other Breast Diseases

The above list describes the most common breast cancers, but there are a few less-common types you should know about, and some other breast diseases that are sometimes confused with breast cancer.

Paget’s disease. This rare breast cancer starts in the milk ducts and then spreads to the skin of the nipple and areola. It can look like an eczema rash.

Lobular carcinoma in situ. Despite the word “carcinoma” in the name, lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS) is not cancer. In LCIS, cells do grow abnormally in the milk glands of the breast, but they do not invade other tissues. Although this condition isn’t cancer, it is a sign that a person is at increased risk for developing cancer in either breast in the future, and you’ll most likely need more frequent screenings.

Phyllodes tumor. These rare tumors begin in the connective tissue of the breast. While they can occur in women of any age, they are most common in women in their 40s. Having Li-Fraumeni syndrome, a rare genetic condition, is a risk factor for developing these tumors. But not all phyllodes tumors are actually cancer—about 75% of them are benign. Usually, these tumors are fast-growing but painless breast lumps.

Breast angiosarcoma. This is a rare form of cancer that begins in the cells of the blood vessels and lymph vessels. Often, it occurs 8 to 10 years after you have received radiation treatment to your breast as a complication of that therapy. Angiosarcomas may appear as purple nodules or lumps.

Inflammatory Breast Cancer

Inflammatory breast cancer (IBC) is a very rare form of breast cancer, accounting for only about 1% to 5% of all breast cancers in the U.S. That said, IBC is very aggressive and fast-moving, according to the National Cancer Institute, which means it’s usually diagnosed when it is in an advanced stage. It occurs when cancerous cells—typically from an invasive ductal carcinoma, meaning it started in the milk ducts of the breast—have spread to lymph vessels in the skin. This can make the skin of your breast look red, swollen, and sometimes dimpled like the skin of an orange. Sometimes, it’s even misdiagnosed as mastitis, which is a noncancerous infection of the milk ducts.

With IBC, it can be hard to diagnose because it can be difficult to detect on a mammogram, and you may not be able to feel a lump. Plus, dense breasts are common in women with IBC, and dense breasts can also make mammogram screenings tricky.

This form of breast cancer tends to be more common in younger women and those who are African-American.

Triple-Negative Breast Cancer

When diagnosing your breast cancer, your doctor will do a series of tests to determine whether your cancer is sensitive to certain types of receptors. There are three of these receptors that are common in breast cancer:

Receptors for the hormone estrogen

Receptors for the hormone progesterone

And a protein called human epidermal growth factor (HER2)

This information helps your doctor tailor your treatment to attack your specific cancer. But what if your cancer doesn’t have receptors for any of these three things?

That’s when you get a diagnosis of triple-negative breast cancer. This type of cancer makes up about 10% to 15% of all breast cancer cases, per the American Cancer Society. It’s most common in women under 40, women who have the BRCA1 gene mutation, and African-American women.

Unfortunately, triple-negative breast cancer has fewer treatment options than breast cancers that do have one of those three receptors, because many breast cancer drugs target those three things. Triple-negative also tends to be more aggressive than other breast cancers. But that doesn’t mean there’s no hope—traditional chemotherapy can still be an effective treatment for triple-negative cancer.

Metastatic Breast Cancer

When breast cancer spreads to parts of the body beyond the breasts and nearby lymph nodes, it’s called stage IV or metastatic breast cancer. Usually, breast cancer is caught before it reaches this stage—only about 6% of people are first diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer, per the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

This advanced form of breast cancer most often makes its way to the bones, lungs, and liver, but other organs such as the brain can also be affected.

While metastatic breast cancer can be difficult to treat and is not considered curable, there are treatment options that can extend your life and improve its quality—and these treatments are improving all the time thanks to science. The go-to therapies to treat metastatic breast cancer are systemic therapies, meaning drugs that target the whole body. These may include hormone therapy, chemotherapy, targeted drugs, immunotherapy, or a combination of these options. Sometimes, surgery or radiation are also used.

Your health-care team will help determine the best treatment for you based on characteristics of your specific cancer. For example, knowing whether your cancer is hormone receptor-positive or -negative, HER2-positive or -negative, or triple-negative can help your doctor tailor your treatment to be most effective.

Who Gets Breast Cancer?

The truth is, almost anyone could theoretically develop breast cancer at some point in their life, regardless of age, race, sex, and other factors. That said, breast cancer does tend to target some groups more than others.

The majority of people diagnosed with breast cancer are women who are 50 or older, according to the CDC, but men can get it, too. Read more about Male Breast Cancer. When it comes to race, white women are most often affected, closely followed by Black women.

What Causes Breast Cancer in the First Place?

As we mentioned up front, breast cancer develops when cells in the breast start to grow and divide in a way they shouldn’t, ultimately creating a mass called a tumor. Cancerous cells may take root in the connective tissue, milk ducts, or milk-producing glands (lobules) of the breast after puberty. But what exactly triggers breast cells to grow out of control isn’t well understood. Scientists do know that certain factors and habits can interfere with a cell’s instruction manual, a.k.a. its genes, according to the American Cancer Society. If something blocks its signal to stop dividing, or messes with its ability to repair DNA damage, those abnormal cells will just keep on going. Read more about Breast Cancer Causes.

What Are the Risk Factors for Breast Cancer?

Every person's risk is different and depends on factors such as genetics, family history, lifestyle, and other issues. But the average woman has about a 12% chance of developing breast cancer at some point in her life. The average age of diagnosis is 62.

Here are some of the most common risk factors for breast cancer.

Family History

While most folks who get breast cancer don’t have a family history of disease, having a relative with a history of breast cancer does raise your risk—particularly if your relative was diagnosed at a younger age. If you have a first-degree relative—a mother, sister, or daughter—with a history of the disease, your own risk is almost doubled. If you have two first-degree relatives with a breast cancer history, your risk is increased by about three times. If you’re a woman with a father or brother who has had breast cancer, this also puts you at greater risk.

Genetics

There are certain genetic mutations that can increase your risk of breast cancer, too. The most common are BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations, and other, less common troublemaker genes include ATM, TP53, PTEN, CHEK2, STK11, CDH1, and PALB2.

Women with a BRCA1 or 2 mutation have a 45% to 72% risk of developing breast cancer in their lifetime. Normally, these genes help prevent that abnormal growth; but when they’re damaged, it’s harder for the body to short-circuit tumor development.

Not everyone needs to be tested for these mutations, but those with certain types of family history (such as having two first-degree relatives with breast cancer, or one if you have Ashkenazi-Jewish heritage) should. So ask your doctor at your next checkup if you should consider genetic screening to get better handle on your breast cancer odds.

If it turns out that you do have one of the mutations, you'll be able to work with your doctor on a plan to get those risk numbers down.

Age

Simply getting older increases the risk of developing breast cancer, and most cases of this illness happen in people 55 years or older. Sometimes it takes decades of little gene mutations to accumulate before one finally tips the balance and triggers a tumor.

Race and Gender

While people of any gender, including men, can get breast cancer, it’s mainly a disease that occurs in women. In the U.S., fewer than 1% of breast cancer diagnoses occur in men. (Read more about Male Breast Cancer, here.)

Your race can also impact your risk of getting breast cancer. White women are most likely to develop breast cancer, with incidence rates at 130.8 per 100,000 women. The next most-commonly affected racial group is Black women, at 136.7 per 100,000 women. That said, Black women are more likely to develop this cancer under age 45 than are white women, and Black women are more likely to die of this cancer at any age (health disparities in this community may partly explain why, some research suggests). However, if you are Asian, Hispanic, or Native American, your risk of breast cancer is lower.

Menstrual History

Most breast cancers are fueled by the hormones estrogen and progesterone, so the longer a woman is exposed to reproductive hormones, the higher her risk of breast cancer. Women who started their periods before age 12 have about a 20% higher chance of developing breast cancer than someone who started after age 14.

Late Menopause

Similarly, hitting menopause after age 55 increases the odds by about 30% versus going through this transition 10 years earlier.

Hormone Treatments/Therapy

Taking certain hormonal therapies, whether for the treatment of menopausal symptoms or as birth control, may also increase your risk of breast cancer. For example, combined estrogen-progestin hormone therapy (EPT) for menopause symptoms can raise your risk. The longer you take EPT, the greater your risk. That said, your risk drops back to normal levels within three years of stopping EPT. Women who take estrogen-only hormonal therapy (EPT) don’t have this increased risk.

A history of using certain oral contraceptives for birth control is also linked to a very small (7%) increase in risk.

Body Weight/Fat

In general, if you are considered overweight or obese after menopause, your risk of breast cancer is increased. Here's a little-known fact about fat: It produces estrogen. So the more you have, the higher your hormone levels tend to be.

One study found that if a woman has been diagnosed with breast cancer, her risk of being diagnosed with a second primary cancer increases as her weight increases.

Another study in JAMA Oncology found that in post-menopausal women, the risk of an estrogen-sensitive tumor was about twice as high in those with the highest percentage of body fat compared to the lowest. This was true even for women who had a “healthy” body-mass index. That’s why it’s important to get regular exercise. In fact research shows that getting regular physical activity is linked to a lower risk of breast cancer.

Diet

Eating an unhealthy diet may increase your risk of obesity, and therefore breast cancer, according to a 2018 review in Current Breast Cancer Reports. While there have been many studies that show that eating a healthy diet can reduce your risk of cancer overall, there’s no clear link between any specific food and increased breast cancer risk.

For example, it’s a myth that sugar makes cancer cells grow faster, per the American Cancer Society. That said, a diet high in sugary drinks and foods may lead to weight gain, which does up your breast cancer risk. But eating the occasional sweet treat is unlikely to cause a problem (phew!).

Alcohol Consumption

An occasional alcoholic beverage is fine, but even moderate drinking (one to two drinks a day) may increase the risk of breast cancer by about a third to a half, according to a study in Current Breast Cancer Reports.

Reproductive History

Whether you have ever been pregnant, and at what age, can affect your breast cancer risk by changing your levels of and exposure to hormones. A study in the International Journal of Cancer found that women who never had children were 1.3 times more likely to develop the disease. Women who had their first baby after age 35 were 1.4 times more likely to get breast cancer than those who had a kid before age 20. Still, the right time to have a baby is whenever you say it is—which may be never.

Dense Breast Tissue

Some women have denser breasts than others—meaning they have a higher amount of glandular and fibrous tissue compared with fatty tissue in their breasts. A high breast density can increase your risk of breast cancer 1.5 to twofold, compared with women who have average density. Plus, having dense breast tissue can make tumors harder to see on mammograms.

A History of Breast Cancer or Breast Lumps

It’s not just family history that puts you at risk—a personal history of breast cancer is also a risk factor. If you’ve had breast cancer in one breast in the past, you’re slightly more likely to develop a new cancer in either your other breast or a different part of that same breast in the future. This risk is slightly higher for younger women. Additionally, if you’ve ever had a family member with ovarian cancer under age 50, your risk of breast cancer may also be increased, per a 2017 study in Gynecologic Oncology.

Your risk of breast cancer is also increased if you have a history of noncancerous (benign) breast disease, such as lumps or cysts. For example, a study presented at the 12th European Breast Cancer Conference in 2020 found that women who had benign breast disease had a 1.87- to 2.67-fold higher chance of getting breast cancer than women with no history of benign breast disease.

Radiation Exposure

If you’ve been treated in the past with radiation to the chest for another cancer, such as a type of lymphoma, you may have a higher risk of breast cancer. Your risk is most increased if you had radiation when you were a teenager or young adult, whereas radiation treatment after age 40 doesn’t appear to increase your risk.

Diethylsibestrol (DES)

Diethylsibestrol (DES) is a drug that is a synthetic form of estrogen. It was given to some pregnant women in the U.S. between 1940 and 1971 to help prevent miscarriage and preterm birth. Unfortunately, these women have a higher risk of getting breast cancer, likely due to the increased exposure to estrogen. If your mother took DES while they were pregnant with you, your risk is also higher.

Do I Have the Symptoms of Breast Cancer?

Some breast cancers cause no obvious symptoms at all—which is why regular mammography screening is so important. (The American Cancer Society says women need yearly mammograms starting at age 45 but should have the option of beginning annual screening at 40.)

Sometimes though, these tumors do make themselves known to you, so it helps to have a sense of what to look for. Having any of the following symptoms does not necessarily mean you have cancer. (Read more about Breast Cancer Symptoms, here.) Still, if you have any of the issues below, consider it a signal to call your doctor:

Lumps and swelling. Many women have naturally lumpy breasts. You should take note of any lumps you feel or see in your breasts—but if both boobs have similar lumps in similar places, or they come and go with your menstrual cycle and are smooth and rubbery, they’re likely just cysts or other normal clumps of tissue. The lump to pay most attention to is one that’s new, only on one side, and doesn’t go away. Sometimes more advanced breast cancers that have spread to the lymph nodes can also cause swelling, tenderness, or a mass in the armpit or by the collar bone. Any thickening or swelling of part or all of one breast should also be checked out.

A hard, marble-sized spot under the skin. Another thing to know: Although tumors can feel squishy and smooth to the touch, cancerous lumps often have irregular edges and feel hard and immovable, like a pebble or marble.

Change in breast size/shape/curve. Unexplained changes in the size or shape of your breast should also be checked out by a health care provider.

Pain. Many women experience breast tenderness that comes and goes during certain times of the menstrual cycle, but new pain in the breast or armpit that doesn’t go away with your period should be checked out.

Inverted or retracted nipple. A newly retracted (or sunken in) nipple is a symptom in some cancers. A tumor can cause inflammation and scarring that tugs that tissue inward.

Nipple discharge. Sudden nipple discharge—especially fluid that’s bloody—in someone who isn’t breastfeeding or had a baby in the last year may be a sign of breast cancer and should be checked out.

Skin changes. If you notice redness, peeling, flaking, or dryness on the skin of the breast or the nipple, it may indicate breast cancer. An eczema-like rash around the nipple can be a sign of Paget’s disease. Redness, warmth, swelling, or dimpling could point to inflammatory breast cancer.

How Do Doctors Diagnose Breast Cancer?

A doctor diagnoses breast cancer using a few different tools. These are some of the more common approaches you can expect.

Imaging Tests for Breast Cancer

The first course of action is to take a look inside your breast tissue, which can be done in several ways through imaging technology:

Mammogram. When you hear breast screening, you probably think of mammograms—that’s because this is the most common screening method for breast cancer and usually the go-to option for a first screening. Most women should start getting regular screening mammograms by age 50, per recommendations from the American College of Physicians, although high-risk women may need to start earlier. These X-ray imaging tests look for masses or small white dots known as calcifications. If a doctor suspects breast cancer, they will order a diagnostic mammogram to further explore any changes in the breast. During a diagnostic mammogram, a radiologist will often look at the images immediately while you wait, in case they want to take additional pictures, or they'll use especially “magnified” views to really zero in on a specific area.

Ultrasound. Sometimes the doctor will want to get a different or more-detailed picture of your breast and will order an ultrasound (using sound waves) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to get more information about a suspicious lump or spot. Ultrasound is a great option for following up on a suspicious lump because the sound waves bounce back differently off a fluid-filled cyst, versus a solid lump that’s more likely to be cancer.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Women who are at high risk for breast cancer sometimes need an MRI along with their regular mammograms. That’s because an MRI can “see” some cancers that a mammogram will miss. That said, skipping a mammo and just having an MRI isn’t a good idea, because MRI can miss other cancers that will show up on a mammogram! Sometimes, MRIs are also used as a follow-up to a breast ultrasound to get more information.

Breast Biopsy for Breast Cancer

During a biopsy, the doctor will take a bit of fluid or tissue from the breast and test it for abnormalities. There are a couple different types of biopsies:

Fine-needle aspiration. In this least-invasive option, a doctor inserts a skinny, hollow needle into the lump to remove some cells. Your doctor can then look at these cells for signs of cancer.

Core needle biopsy. This type of biopsy uses a larger, hollow needle to assess suspicious breast changes. If breast cancer is suspected, this is often the biopsy method of choice since the larger needle can remove a greater amount of tissue. It doesn’t require any surgery. Again, your doctor may use an imaging test to help guide the needle if necessary.

Surgical (open) biopsy. This type of biopsy may be done if results from a core needle biopsy or fine-needle aspiration are unclear and your doctor needs more information. In a surgical biopsy, your doctor uses surgery to remove the entire suspicious lump (called an excisional biopsy) or just part of it (called an incisional biopsy) to investigate it for cancer.

Lymph node biopsy. If your doctor needs to see whether your breast cancer has spread to your lymph nodes (such as those under your arms), they may also do a core needle biopsy or fine-needle aspiration on one or more of those lymph nodes.

Image-guided biopsy. An image-guided biopsy is when your doctor uses ultrasound, mammography (called a stereotactic biopsy) or other imaging techniques to help guide the needle during a biopsy procedure. For example, this may be done during a fine-needle aspiration or core needle biopsy if the lump is hard to feel or find and your surgeon wants to better guide their aim.

Vacuum-assisted biopsy. During a needle biopsy, your doctor may use a suction device to help get a better sample.

Analyzing a Biopsy Sample

Your team of doctors will study the biopsy sample taken from your breast to identify any specific features to help determine your best treatment. These features include:

Tumor features. Under a microscope much can be revealed, including whether a tumor is invasive or non-invasive (in situ), lobular, or ductal. Doctors can also determine whether or not the tumor has spread to your lymph nodes.

HER2 status. If a biopsy shows that your tumor is cancerous, more testing is done to determine what kind of cancer it is. HER2-positive breast cancers overproduce the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) protein, which can speed tumor growth. Those who test positive receive certain targeted medications that can block those signals.

ER and PR. Breast cancers that depend on estrogen receptors (ER) or progesterone receptors (PR) to grow are called hormone receptor-positive tumors. If your biopsy shows your tumor is either, doctors will run further tests. These cancers can be treated with hormone-therapy drugs and often have a better prognosis than other tumors, according to the American Cancer Society. A majority of breast cancers are hormone-receptor positive.

Grade. Grade describes a tumor’s cells—if they look different from healthy cells, and how fast or slow they’re growing. There are three grades: grade 1 (well-differentiated, or closest to healthy-looking cells), grade 2 (moderately differentiated), and grade 3 (poorly differentiated, or very different from healthy-looking cells).

If both hormone receptor and HER2 tests are negative, the breast cancer is classified as triple-negative. Triple-negative cancers tend to be more aggressive than other types of breast cancer, though experts aren't exactly sure why, and there are fewer targeted treatments.

Additional Tests After a Biopsy

Your doctor may also run other blood tests to check on how different systems of your body are functioning. This may be done at various types throughout your cancer diagnosis and treatment.

Complete blood count (CBC). A CBC looks at the number of different cell types you have in your blood, including red and white blood cells. The goal is to make sure your bone marrow is functioning as it is supposed to.

Hepatitis tests. In some cases, your doctor may test your blood to see if you have an active hepatitis B or C infection. That’s because undergoing chemotherapy with an active infection could result in increased liver damage.

Blood chemistry test. Your doctor may run a blood chemistry test, which reveals how well your kidneys and liver are functioning.

MammaPrint and other tests. After a biopsy, your doctor may run additional tests on your cells to gather more information about your cancer, according to the American Cancer Society. For example, Oncotype DX, Pam50 (Prosigna), and MammaPrint are tests that look at the genes in your breast cancer. The information these tests reveal can help your health care team personalize your treatment to your specific cancer.

What Are Breast Cancer Care and Treatment Options?

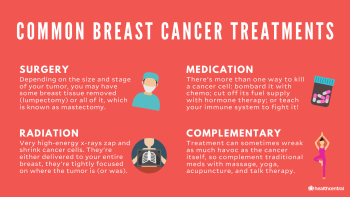

Most breast-cancer treatment includes surgical removal of the tumor. But many people will need more care after that. A lot of people consult with a team of different types of doctors including oncologists and breast surgeons before deciding what to do.

The best combination of treatments for your breast cancer depends on your specific circumstances. Your health care team will look at different factors, including your age, the stage of your cancer, the type of cancer (including its sensitivity to hormones), your preferences, and more to determine the best course of action. Read more about Breast Cancer Treatments.

Surgery for Breast Cancer

A range of surgical procedures, some more extensive than others, are available to remove breast cancer tumors or reconstruct the breast after a tumor has been removed. They include:

Lumpectomy. Just the tumor and some of the tissue around it is taken out. This can be a good option for people with cancers that are small, relative to the breast and are not multiple within the breast, as it can help conserve the breast. Many patients with spread to nodes may also be candidates.

Mastectomy. All the breast tissue (and sometimes the nipple and/or skin of the breast) is removed. It’s often recommended when there are several areas of cancer in the breast, or when the tumor is very large compared to the amount of healthy breast tissue. There are a few different types of mastectomies, which are listed below.

Simply/total mastectomy. A simple mastectomy removes the whole breast, along with the nipple, areola, and skin. Sometimes, underarm lymph nodes may be removed too. A double mastectomy is when both breasts are removed—this is often done if you have a BRCA mutation or are otherwise at increased risk of breast cancer.

Partial mastectomy. This type of mastectomy is like a more extensive form of a lumpectomy. Your surgeon removes the cancerous breast tissue and some of the normal tissue that surrounds it. Sometimes, you may hear this called a quadrantectomy or segmental mastectomy, or “breast-conserving” surgery.

Skin-sparing mastectomy. This type of mastectomy leaves most of the skin over your breast but removes the breast tissue, nipple, and areola. This option results in less scarring and a more natural reconstructed breast. That said, not all tumors are good candidates for this type of surgery.

Nipple-sparing mastectomy. In this surgery, your doctor removes the breast tissue but leaves the breast skin and nipple intact. Again, this may not be an option for all women, but it is often a preferred choice before breast reconstruction surgery.

Radical mastectomy. This is when your surgeon removes the whole breast, the underarm lymph nodes, and the chest wall muscles beneath the breast. It used to be a common form of surgery, but it’s not done very often anymore because other less extensive surgeries are just as effective. For example, a modified radical mastectomy is when a simple mastectomy is done and the underarm lymph nodes are also removed, but not the chest wall muscles.

Lymphadenectomy. This procedure entails removal of some or all of the lymph nodes under the arm (called axillary lymph nodes). This may be required if the tumor has spread beyond the breast itself. This is also sometimes called lymph node dissection. You may also hear the term sentinel lymph node biopsy, which is when the sentinel lymph node—the first lymph node to be affected by the spreading cancer—is removed in surgery.

Breast reconstruction surgery. If you’ve had a mastectomy, you may want to have breast mounds surgically reconstructed to look similar to how they did before. This is an option for most but not all people who have mastectomies. It’s important to discuss your preferences to do this before your mastectomy so your surgical team can plan ahead.

Chemotherapy for Breast Cancer

Chemotherapy medications are used to kill or shrink cancer cells. Some tumors respond better to chemo than others—tests done on your specific cancer cells will help you and your doctor decide whether these drugs should be part of your treatment plan. Chemo is usually given as an IV infusion or injection at a clinic or doctor’s office. Doses are given in bursts—or cycles—of a few weeks at a time so that patients are able to rest and recover from each treatment before having another. The length of time a person will need chemotherapy treatments can vary, but it often lasts anywhere from three to six months.

Sometimes, chemotherapy is given in combination with other treatments, according to the American Cancer Society. When chemo is given before surgery, it’s called neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Your doctor may go this route to try to shrink your tumor first so that surgery doesn’t have to be so extensive. When chemo is given after surgery, it’s called adjuvant chemotherapy. This might be done to kill any cancer cells that may have been left behind after a surgery.

Hormone Therapy for Breast Cancer

Hormonal therapies are often used to treat hormone-positive cancers in order to cut off the supply of hormones the tumors need to grow and spread. These medications are usually taken for a long time—between five and 10 years.

There are a few main types of hormone therapies for hormone-receptor positive breast cancers:

Estrogen receptor-blocking drugs. For breast cancers that are sensitive to the hormone estrogen, blocking estrogen receptors with medication can be an effective way to fight cancer growth. Such medications include tamoxifen and fulvestrant (Faslodex).

Estrogen-lowering treatments. Similarly, some effective therapies work by helping to reduce your estrogen levels to help prevent cancer growth. One drug in this category is called an aromatase inhibitor, which works by blocking the production of estrogen in the body. Other treatments that can reduce estrogen levels include ovarian suppressing treatments, such as oophorectomy (surgery that removes your ovaries), chemotherapy medications, and drugs called luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) analogs (drugs that stop your body from sending a signal to the ovaries to make estrogen).

Other hormone therapies. Less commonly, other forms of hormone therapy may be used, such as megestrol acetate (a progesterone-like medication), male hormones called androgens, and high doses of estrogen.

It’s important to note that hormonal therapies can have an effect on your fertility. For example, oophorectomy causes permanent menopause. Other hormonal therapies may cause only a temporary halt in the production of eggs in your ovaries, but some women do have trouble getting pregnant even after stopping hormone therapy. That’s why it’s important to talk to your doctor about options for preserving fertility before starting treatment.

Targeted Therapies for Breast Cancer

Targeted drugs work by—you guessed it—targeting a specific aspect of the cancer to better block cancer growth. For example, a drug may target the genes of your specific cancer, a protein that it’s producing, or other characteristics of your specific tumor. Your doctor will run different tests to help determine whether there is a targeted drug that may work well for you.

One of the big pros of this type of treatment is that it limits the damage to healthy cells, unlike chemo, which can cause a lot of side effects by damaging healthy tissues in addition to attacking the cancer. Targeted therapies can be given as injections, IV infusions, or in pill form and some may be given for up to a year.

Here are some of the potential targeted drugs for breast cancer.

HER2-Targeted Drugs

If your doctor has identified your cancer as HER2-positive, they may prescribe one of these targeted drugs:

Trastuzumab (Herceptin)

Pertuzumab (Perjeta)

Pertuzumab, trastuzumab, and hyaluronidase-zzxf (Phesgo)

Neratinib (Nerlynx)

Ado-trastuzumab emtansine or T-DM1 (Kadcycla)

Other Targeted Drugs

Other types of targeted medications your doctor may prescribe include:

Alpelisib (Piqray)

Drugs that target the CDK4/6 protein: abemaciclib (Verzenio), palbociclib (Ibrance), ribociclib (Kisqali)

Lapatinib (Tykerb)

Tucatinib (Tukysa)

Sacituzumab govitecan-hziy (Trodelvy)

Enctrectinib (Rozyltrek) and larotrectinib (vitrakvi)

Olaparib (Lynparza)

Talazoparib (Talzenna)

Everolimus (Afinitor)

Immunotherapy for Breast Cancer

Other medications may be used to encourage a person’s own immune system to kill cancer cells. These are called immunotherapy drugs, or biologic therapy, according to the American Society of Clinical Oncology. Like other targeted drugs, immunotherapies typically don’t damage healthy cells as much as chemotherapy does. That said, as with any drug, there are potential side effects, such as skin rashes, flu-like symptoms, and diarrhea. Currently, there are two immunotherapy drugs approved to treat certain advanced breast cancers:

Atezolizumab (Tecentriq). This drug combines the immunotherapy drug atezolizumab with a chemotherapy drug to help target locally advanced triple-negative breast cancer and metastatic triple-negative breast cancer.

Pembrolizumab (Keytruda). This immunotherapy medication treats certain types of metastatic breast cancer that can’t be treated with surgery. It may be used in combination with chemotherapy drugs in some cases to treat metastatic or locally recurrent triple-negative breast cancer.

Radiation for Breast Cancer

Very high-energy X-rays are delivered to the breast in order to wipe out cancer cells, shrink tumors, and/or help prevent breast cancer from growing back after surgery. Whether you need radiation depends on a lot of factors. If you have a lumpectomy instead of a mastectomy, for example, you will likely need radiation to zap any malignant cells that may have been left behind, lowering the chances that tumor will grow back. Some women will need radiation after mastectomy, as well.

Radiation is either done on your entire breast, or just the part where the tumor was located. If your doctors decide that you need whole-breast radiation, you’ll get a treatment five days a week for three to six weeks. If only part of your breast needs radiation, you’ll typically need one or two treatments a day for three to five days.

There are a few different types of radiation therapy used to treat breast cancer:

External beam radiation. This form of radiation is the most common type used to treat breast cancer. It’s kind of like getting an X-ray, but with stronger radiation. It uses a machine outside of the body to target the radiation to the correct area with a beam.

Internal radiation. This type of radiation, sometimes called brachytherapy, is a type of radiation therapy that works from inside the body to target a part of the breast. Small tubes or catheters deliver this radiation to the area where the cancer was using small pieces of radioactive material. Usually, it’s done in women over 45 who had DCIS or early-stage invasive breast cancer removed in a lumpectomy.

Intraoperative radiation therapy (IORT). This is a type of partial-breast radiation that is performed during breast cancer surgery right after the cancerous area has been removed and before the incision is closed. It uses the same machine as external beam radiation, but it delivers low-energy X-rays or electrons to limit the radiation dose.

Hypofractionated radiation therapy. This form of radiation is similar to external beam radiation but can be done in fewer sessions (15 to 19 compared with 25 to 30) because a higher dose of radiation is delivered.

3D-conformal radiotherapy. This form of radiation therapy uses special machines to better target the tumor area and is given two times per day for five days.

Other Types of Breast Cancer Therapies That Can Help

There’s a reason people talk about the war against cancer: Because treatment turns your body into battleground. So when you’re going through it, do whatever you need to feel comforted, supported, and less stressed out. Massage, yoga, acupuncture, and/or plain old talk therapy can be the balm that protects you from any collateral damage.

Does Breast Cancer Treatment Cause Complications?

It can. Different treatments have different risks and side effects, but these are some of the most common ones, according to the CDC:

Potential Complications From Breast Cancer Surgery

Pain

Loss of sensation in the chest or remaining breast tissue

A type of swelling called lymphedema. After having radiation therapy—or lymph nodes removed during surgery—lymph fluid can start building up in the arms, hands, breasts, or torso.

Potential Complications From Chemotherapy

Nausea

Mouth sores

Hair loss

Higher risk of infections

Reduced appetite and/or weight loss

Brain fog or trouble with concentration and memory (often called “chemo brain”)

Potential Complications From Hormone Therapy

Headache

Mild nausea

Hot flashes

Vaginal dryness

Vaginal discharge

Hot flashes

Night sweats

Increased risk of blood clots

Mood swings

Potential Complications From Targeted Therapies

Fatigue

Hair loss

Mouth sores

Nausea

Increased cholesterol or blood sugars

Increased risk of infection

Heart problems

Side effects of breast-cancer treatment can be pretty unpleasant, but these days, doctors have a lot of ways to help ease, from anti-nausea medications to ones that boost your immunity. Don't worry about putting up a brave front. If you're struggling with symptoms, let your doctors know so they can help you find some relief.

What Is the Outlook for Breast Cancer?

When you receive a diagnosis of breast cancer, one of the first thoughts racing through your mind is likely, “What’s going to happen to me? Will I get better?” The good news is that breast cancer treatments are better than ever, and they are improving all the time thanks to the latest research.

Below, we’ve listed the five-year survival rates for different stages of breast cancer based on available data from the National Cancer Institute (NCI). Note that the NCI doesn’t track this data based on stages 0-4—instead, they group cancers based on whether they are localized, regional, or distant. Here’s what those terms mean:

Localized: There’s no sign that the cancer has spread beyond the breast.

Regional: Cancer has spread beyond the breast to nearby lymph nodes or other structures.

Distant: Cancer has spread to distant areas of the body, like the bones, liver, or lungs.

Overall, for all breast cancers combined, the five-year survival rate is 90%. That means that compared to the overall population, women with breast cancer are 90% as likely to live for at least five years after diagnosis on average.

And remember: These stats are just estimates—talking with your doctor about your specific case and potential outlook is a must. That’s because your treatment outlook depends on a ton of different personalized factors, such as your age, race, specific type of breast cancer, and more. Here are the five-year survival rates by stage:

Localized: 99%

Regional: 86%

Distant: 29%

You also may have heard that having cosmetic breast implants affects your chances of survival if you get diagnosed with breast cancer. While it’s true that some research has pointed to this risk, a 2013 systematic review in BMJ urged that we interpret this data with caution since some of the studies did not account for other factors beyond having breast implants when assessing survival rates. That said, the link may exist because having breast implants can make it trickier to detect a cancerous breast lump at an early stage when breast cancer is easier to treat. If you’re concerned about the impact of breast implants on your cancer risk, talk with your doctor.

Male Breast Cancer

While the biggest risk factor for getting breast cancer is being a woman, it’s true that men can also develop breast cancer. In fact, in 2019 Beyonce’s dad became one of the 2,650 men diagnosed in the U.S. annually. That’s because men also have breast tissue in their bodies—a little known fact. That said, it’s pretty rare: Fewer than 1% of breast cancer cases in the U.S. occur in men.

Unlike in women, breast tissue in men doesn’t tend to grow after puberty. That said, it’s still possible for cancer to develop in these cells. The most common types of breast cancer in men, per the American Cancer Society, are:

Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). DCIS, the earliest form of breast cancer that starts in the ducts, makes up about 10% of all male breast cancer cases, and thankfully, surgery can cure it almost all of the time.

Invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC). IDC is also the most common breast cancer in women. In men, it makes up at least 80% of all breast cancer diagnoses. These cancers are those that begin in the ducts but then spread into other breast tissues. In men, this usually happens fairly close to the nipple since there’s less fatty tissue than in women.

Paget disease of the nipple. This is a type of breast cancer that begins in the ducts of the breast but then spreads to the nipple, and sometimes the dark circle around the nipple called the areola. While it only accounts for about 1% to 3% of female breast cancers, it’s slightly more common in men at 5%. Symptoms include skin changes on the nipple, including a scaly, red, crusted appearance and itching, bleeding, or oozing.

Invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC). Only about 2% of all male breast cancers are ILCs, which means they start in the milk-producing glands in the breast called lobules. It’s so rare because men don’t often have many lobules in their breast tissue.

Extremely rarely, men can also develop inflammatory breast cancer or lobular carcinoma in situ, which are other breast cancer subtypes.

What’s Life Like for People With Breast Cancer?

Living day-to-day after being diagnosed with breast cancer can be full of fear and anxiety, plus pain or other really-not-fun side effects from treatment. You may also have to deal with people who don't understand the condition and can't fully grasp what you're going through. But here’s the good news: Because breast cancer is a relatively common illness and because there are so many excellent treatments, there are a lot of people who understand your situation and can help.

Take things one step at a time: Educate yourself about breast cancer, never be afraid to ask your medical team questions, and enlist the help of a friend or loved one to go to appointments with you. Breast-cancer treatment can be complex and the terminology confusing. It can be hard to keep everything straight when you are feeling unwell or are scared—your appointment buddy can take detailed notes and write down questions for you to ask next time.

Emotional Health

This diagnosis can turn your life upside down. But you’re going to be making some of the most important decisions of your life over the next few months, and stress and depression can interfere with your healing process. Here’s how to fight back.

Work stress-relief into your daily life. Negative emotions can impact your ability to make thoughtful decisions, as well as lead to stress that can suppress your immune system. So be sure to incorporate activities that help you quiet your mind such as meditation, deep breathing, exercise, journaling, or any other method that works for you.

Speak up! Talking with friends and family about what you're going through can help you feel less alone. It’ll also give them a chance to offer support. And when they do, take it. If you’re too tired to cook, let them bring you dinner. If you want company at a chemotherapy treatment, let them drive you to the clinic and stay and chat during your infusion.

Consider attending a support group or talking to a therapist. Being diagnosed with breast cancer is frightening—even if yours is caught early and you have a sunny prognosis. No one can understand exactly what you’re going through quite like someone who’s experienced it. Many larger hospitals and cancer centers have free support groups for patients. Try one out.

Sex Life

Cancer involves you in the fight of your life, and it’s often difficult to think about anything else, including sex. Plus, the way you feel about your body and how it looks can change a lot after lumpectomy or mastectomy surgery.

Treatments like chemotherapy or hormone therapy can also interfere with sexual desire or function. But you don’t have to just sit back and take it. A good first step is to talk to your doctor. Most women deal with some sex-life changes and interruptions during or after breast-cancer treatment.

Your doctor will not be surprised or embarrassed when you bring it up! And she can help: There are medications and other fixes she can recommend to help ease sexual side effects of medications; plus she can refer you to a support group for other breast-cancer survivors or to a counselor who is skilled at helping survivors ease back into their normal lives—orgasms included.

Breast Cancer Prevention

If you’re reading this and you haven’t been diagnosed with breast cancer, you may be wondering if there are steps you can take to reduce your risk and stay as healthy as possible. The answer is a resounding yes! Here’s the latest evidence on breast cancer prevention.

Lifestyle Factors

While there are some risk factors for breast cancer that you cannot change, such as your genetics, there are some you have control over, like alcohol consumption. That said, there are also factors that evidence shows are protective against breast cancer, according to the American Institute for Cancer Research. Here are some things you can do to live a healthier lifestyle and reduce your risk of getting breast cancer:

Exercise. Studies show that getting enough exercise can help protect you against breast cancer, and not exercising enough can increase your breast cancer risk. So getting enough physical activity should be a top priority. Current guidelines suggest getting at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity per week. Moderate-intensity activities are things like brisk walking, yoga, doubles tennis, or gardening). Another option is to get 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity activity in per week with activities like jogging, swimming, playing soccer, or taking aerobic dance classes. Grab a buddy to help motivate you and make it more fun!

Reduce your alcohol intake. While many of us love to indulge in a glass of wine now and then, it’s true that drinking alcohol can raise your breast cancer risk. While no alcohol is best if you’re trying to be proactive about breast cancer risk, cutting back to just the occasional drink can still make a difference.

Maintain a healthy weight. Research shows that having excess body fat after menopause raises your risk for breast cancer. Take steps to maintain a healthy weight, such as eating a healthy diet and exercising regularly.

Breastfeed if you are able. Fun fact—breastfeeding can reduce your risk of breast cancer by lowering certain hormone levels in your body. That said, if you’re unable or unwilling to breastfeed, there are still plenty of other things you can do to stay healthy (see above!).

Breast Cancer Screening

One of the best ways you can protect your health is to get breast cancer screenings according to the latest medical guidance. That’s because screening can help catch suspicious areas of breast tissue early and treat them before they become a bigger problem. It could even save your life.

Here are the latest recommendations on breast cancer screening from the American College of Physicians based on your age if you are of average risk, meaning you have no symptoms, no history of cancer, and no high-risk genetic mutations:

Ages 40 to 49: Women in this age group should talk with their doctor about whether they should be screened for breast cancer before 50 and weigh the risks and benefits.

Ages 50 to 74: Women in this age group should be screened every other year with a mammogram.

Ages 75 and up: Women over 75—or women who have a life expectancy under 10 years—don’t need to be screened for breast cancer.

That said, it’s smart to talk with your doctor about a good screening schedule for your personal health history and circumstances—especially if you don’t fall into that “average-risk” category.

Preemptive Treatment

If your doctor has identified you as at very high risk of getting breast cancer, there may be things you can do now to help reduce that risk, including surgery or taking certain medications.

Prophylactic Mastectomy

Some women may choose to get preventive surgery called a prophylactic mastectomy to remove their breasts and lower their risk if they are at very high risk of breast cancer. This surgery can reduce your risk of breast cancer by more than 90%, according to the American Cancer Society. You may be a candidate for this surgery if you:

Have a BRCA1 or BRCA2 genetic mutation

Have a strong history of breast cancer in your family, such as in several close relatives

Had radiation therapy to your chest before age 30

Have already had cancer in one breast, especially if you have a strong family history too

Medications for Breast Cancer

If you’re at high risk of breast cancer, there may be some medications you can take to help lower your risk. This is called chemoprevention. Such drugs include:

Tamoxifen

Raloxifene

Aromatase inhibitors

Your doctor can help explore these options with you, including potential side effects, to determine the best course of action depending on your specific risk factors and circumstances.

Breast Exams

Neither breast self-exams nor clinical breast exams have been shown to reduce the risk of dying from breast cancer, according to the American Cancer Society. In fact, they do not recommend regular self-exams or clinical exams of the breast. That said, they also say there are good reasons to do these exams in some cases. For example, they can be a good opportunity to increase your awareness of what is normal for your body and speak with your doctor about any concerns.

Self-Exams

It’s important to get well acquainted with how your breasts normally feel and look—this is called breast self-awareness. This practice can help you notice any changes such as lumps or pain. If you do notice changes, report them right away to your doctor so they can check them out.

Breast Exams by Your Doctor

Another type of breast exam is a clinical breast exam, which is one done by a doctor or nurse. They will use their hands to feel your breasts and under your arms for changes, including lumps.

Breast Cancer Awareness

Have you noticed an increase in all things pink when October rolls around? That’s because October is recognized as Breast Cancer Awareness Month. The goal of this campaign is to increase support and awareness for breast cancer, including educating the public about the basics of breast cancer to aid in efforts to detect cases early and improve treatment outcomes.

But raising breast cancer awareness shouldn’t be confined to just one month of the year. Since this is the most common cancer among women in the U.S. other than skin cancers, it’s important that everyone know the basics about this cancer. That means knowing when you should start getting breast cancer screening, knowing the basic symptoms to watch for, and more. Because the more we know about breast cancer, the more we can work together to fight it and keep ourselves and our communities healthy.

Where Can I Find Breast Cancer Communities?

There’s a lot of talk about breast cancer but finding and talking to people who know exactly what you’re going through can be just as important as finding a treatment plan that works. Here are some places to start to make connections, find resources, and meet friends.

Top Breast Cancer Bloggers/Instagrammers

Brittney Beadle, @brittneybeadle

Follow because: Breast cancer does not rule her life—she continues to live life to the fullest, with just “a touch of metastatic breast cancer.” One day she’s at chemo, the next day she’s basically a mermaid who lives at the beach.

Maggie Kudirka, @baldballerina, baldballerina.org/

Follow because: She went from the big stage as a ballerina with the Joffrey Concert Group in NYC, to chemo chairs with stage IV metastatic breast cancer. With a double mastectomy behind her, she’s fighting and clawing her way back to the spotlight, one plie at a time.

Dayna Dono, @daynadono, anaono.com/

Follow because: There’s actually a bra for that—and she’s the one to thank for it. She’s the founder and designer of AnaOno—a bra made specifically for women who have had breast-cancer reconstruction, breast surgery, mastectomy, or are living with other conditions that just don’t mix well with other bras.

Umi Marie, @umi_kmarie

Follow because: Dancer, yogi, mom of three, and breast cancer warrior — these are just a few of her titles. But when we scroll her feed, we see: poet. Her words of gratitude and encourage are like mini-mantras to live your life by — and a lot of them stem from her survivorship.

Beth Fairchild, @bethfairchild

Follow because: She’s fearless and fighting stage IV breast cancer. Her campaigns for breast-cancer awareness are fresh and spread like wildfire, and we totally encourage you to blaze that trail with her.

Nalie Agustin, @nalieagustin

Follow because: Motivational YouTuber Nalie Agustin was diagnosed with stage IV breast cancer at just 24 years old. She vlogged all the way through her treatments on her channel and then started The Nalie Show there, where she talks to fellow cancer survivors, celebrities, and other inspiring folks.

Sabrina Skiles, @sabrinaskiles

Follow because: Not that long ago she was a 30-something mom of two boys, following her husband across the country for his dream job, and celebrating a milestone birthday. That all changed overnight when she found a lump in her breast. Now she’s a beautifully mixed bag of mom-chemo-wig-wife-radiation-recovery-life. Her posts, like mini columns, will leave your heart either broken, fulfilled, or both, all at once. Oh, and she shares breast-cancer-friendly recipes, too! Told you she’s worth the follow.

Jessica Boyd, @jessicaaboyd

Follow because: Just because she’s a few years out from her final round of chemo, doesn’t mean she stops fighting the hardest fight of her life against cancer returning. Especially when she has another reason to fight — for her miracle baby, conceived three years after finishing cancer treatments. Join her on the first of every month for a self-breast check (don’t worry, she’ll remind you), and on her fitness journey to stay strong so she can fend of metastatic breast cancer.

Top Breast Cancer Podcasts

Investigating Breast Cancer. This show, from the Breast Cancer Research Foundation, discusses the latest breast-cancer news with top doctors in the field.

The Good Glow. After her breast cancer diagnosis, Georgie Crawford’s perspective on life completely changed. She needed a new outlook—one that brought her back to the basics of self-care and surrounding yourself with positivity. This listen will give you all the good vibes.

Bustin' Out of Breast Cancer. Hosted by Shannon Burrows, a breast-cancer survivor and recovery coach, this podcast shares survivor stories and talks about thriving, not just surviving, in life after diagnosis.

Top Breast Cancer Support Groups and Non-Profits

Living Beyond Breast Cancer. Trustworthy information, community, and support for people with breast cancer and their friends and families—plus ongoing educational programs such as conferences and webinars. There’s also a free online/telephone helpline that will match patients with volunteers for one-on-one support and education.

Young Survival Coalition. The YSC focuses especially on people age 40 and under affected by breast cancer with free educational programs and guidebooks plus active discussion boards, a private Facebook group, and in-person meet-ups.

Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation. One of the best-known breast-cancer advocacy organizations, Komen is a powerhouse fundraiser for breast-cancer research, and offers wide-ranging free services from an online treatment navigation tool to a breast care helpline and information on financial assistance.

Metastatic Breast Cancer Network. A patient-led advocacy organization focusing on the unique needs and concerns of people living with metastatic (or Stage IV) breast cancer. The MBCN offers info on clinical trials and treatments for advanced breast cancer, peer support groups and message boards, and even funds scientific research.

The Breasties. They make breast cancer look cool. “Free retreats, events, and community for women affected by breast and reproductive cancers.”

Stupid Dumb Breast Cancer on Facebook. A community of women going throuhg breast cancer at all different stages. You will get an answer and support on anything you post. Sweet, genuine women wanting to pay it forward and support others.

Additional reporting by Lara DeSanto, Health Writer

Frequenty Asked Questions

How do I check myself for breast cancer?

The best way is to get to know your breasts—how they feel, what they look like, and how they change during your menstrual cycle—and to let your doctor know about any concerning changes. The most common symptom of breast cancer is a lump. Other signs can include dimpled skin, pain or swelling in one breast that's not related to your period, skin inflammation, and unexpected nipple discharge.

What are the chances that I could develop breast cancer?

Every person's risk is different and depends on factors such as genetics, family history, lifestyle, and other issues. But the average woman has about a 12% chance of developing breast cancer at some point in her life. The median age of diagnosis is 62; only about 5% of women with breast cancer are diagnosed under age 40.

What is the breast-cancer survival rate?

Prognosis depends on several things including the stage of cancer, type of tumor, and what treatments are available. But on average, the five-year survival rate for invasive breast cancer is 90%. The 10-year survival rate is 83 percent. The 5-year survival rate for metastatic breast cancer (the type that has spread to other parts of the body) is 27%. But remember, the survival rate for the earliest forms of breast cancer is 99%.

Can men get breast cancer?

Yes. Any person of any gender can get breast cancer, although women are 70 to 100 times more likely to develop the disease than men, according to the American Cancer Society. About 2,600 men are diagnosed each year.

Meet Our Pro Panel

We went to some of the nation’s top experts in breast cancer to bring you the most up-to-date-information possible.

P. Hank Schmidt, M.D., Breast Surgical Oncologist, Mount Sinai, New York, NY

Jonathan Stegall, M.D., Medical Director, the Center for Advanced Medicine, Alpharetta, GA

Zahi Mitri, M.D., Breast Cancer Oncologist, the OHSU Knight Cancer Institute, Portland, OR

More Like This

What to Expect During a Breast MRI

Medically Reviewed

The Stages of Breast Cancer, Explained

Medically Reviewed

Does Breast Cancer Show Up in Blood Tests?

Medically Reviewed

Breast Implant Illness: Can Implants Cause Chronic Disease?

Medically Reviewed